By Pamela Olson

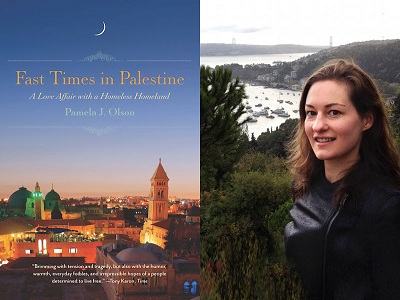

(The following is part of an outtake from Pamela Olson’s book Fast Times in Palestine, published by Seal Press in March 2013. The full story, with photos is posted on her blog.)

A friend from college named Cameron was in Israel visiting family for Passover. He was an adventurous soul, a world traveler and entrepreneur, with curly brown hair, blue eyes, and a slim athletic build. When his family learned I was in the Holy Land, they invited me to their Passover seder — until they realized I lived in Ramallah, at which point they promptly rescinded the invitation.

Cameron was a strong supporter of Israel and hawkish on security issues, but he was embarrassed by his family’s behavior. I told him he could make it up to me by visiting the West Bank for a week and seeing the occupation for himself. To my pleasant surprise he agreed. In order not to upset his family, he told them he was heading to the Sinai for a week.

He arrived in Ramallah just as the Dancing Traffic Cop was beginning his shift in Al Manara. Tall, lanky, and graceful, wearing reflective silver aviator sunglasses, the man didn’t just direct traffic. He made a show of it. Cameron and I watched in amazement as his long arms moved in quick, precise, exaggerated arcs and twirls to match his intricate, impeccable footwork.

Even when he took a break and headed to the coffee stand under the palm trees, he didn’t just walk. He strutted, smiling with his razor-sharp Robocop jaw line, tipping his hat to passers-by as if he were the uncontested king of Al Manara.

Cameron looked at me, demanding an explanation. I could only shrug. I didn’t question it anymore. I just enjoyed it.

* * *

A few days later, Cameron and I took a service taxi to the Dheisha Refugee Camp near Bethlehem. I found a receptionist at the Ibdaa Cultural Center and asked if there was anyone who could show us around the camp.

“Probably you should talk to Jihad,” she said.

Cameron tensed beside me, unable to parse the strange sentence. He didn’t know ‘Jihad’ was a common name in the Arab world.

Jihad arrived a few minutes later. He had a medium build, a light beard, and the sporty wardrobe and tightly-coiled defensiveness of a ghetto youth. He greeted us politely without meeting our eyes and took us on a quick walking tour. It was standard fare for a Palestinian refugee camp — narrow streets, concrete buildings, cramped alleys, and occasional touches of bougainvillea or decorative tiles to lend a whiff of dignity. The residents were mostly from villages west of Bethlehem that had been depopulated and destroyed in 1948. The ruins of their villages were just a few miles away. Their hilly lands had been forested with conifers and turned into an Israeli national park.

Jihad took us back to the Ibdaa Center and showed us a game room where two middle-aged men in tank tops were playing a fierce game of ping pong. When one missed a tough shot he muttered under his breath, “Allahu akbar!”

Cameron looked at me, alarmed. This was another word like jihad that only meant political hate speech in Cameron’s mind. I whispered, “They say Allahu akbar in a lot of different ways. Sometimes ironically. Right now he’s saying it like, ‘Good Lord!’ or ‘God Almighty!’”

“Ah.” Cameron relaxed. He even seemed to smile a little, as if the world had suddenly become slightly less dark.

As Jihad got to know us better, his bored affect began to melt away. He told us a performance would take place that night in the center’s small theater and invited us to attend.

The performers were a group of disarmingly self-possessed children from the camp who sang and danced with the names of their destroyed villages hanging around their necks. They all held keys in their hands, symbols of the homes their parents and grandparents had left behind.

The implication was unmistakable: Sooner or later, one way or another, they would reclaim their birthright and return home. Cameron looked deeply shaken.

* * *

Nablus was our final stop. We made it through the Huwara checkpoint without problems, and Nick met us in Nablus’s main traffic circle. He looked restless and excited as he led us to the Balata Refugee Camp, where he said a militant rally was taking place. Cameron looked anxious but gamely followed.

The crowd thickened as we neared a small stadium packed with onlookers. Nick muttered, “The rally’s being put on by the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. The PA is just starting to assert control over ‘lawless’ areas. Balata Camp is one of them, and it’s an Al Aqsa stronghold.”

“Aren’t the Al Aqsa Brigades part of Fatah?” I asked.

“Yeah, they’re an armed offshoot of Fatah. But they have cells all over the West Bank, and the cells usually have some level of autonomy. Right now Palestinian police can’t even go into the Old City. They don’t dare. It’s the militants’ stomping grounds.”

His eyes widened and his voice dropped further. “The police are coming in now. You see them?”

“Yeah,” I whispered back. “What are they doing?”

“I think they’re just here to assert their presence.” We could see them and the militants eyeing each other with the tension of estranged brothers in the same room. I began to feel nervous. The first big clash between the Al Aqsa Brigades and the PA police might be brewing right here.

A militant started giving a speech. At one point he stopped, stared at the policemen, and fired a single shot in the air. The policemen didn’t react other than clutching their guns more tightly.

We quietly slipped out, and the rally ended later without incident. But it was another harbinger of changing times. Over the next few years, nearly all the militants in Nablus would be finished off, bought off, disbanded, or absorbed into the police.

They still ruled the city now, and as we walked through the Old City, a group of young militants surrounded us and started chatting with us. They didn’t seem threatening, just bored. One of them, a goofy, awkward youth, had a baby face and was missing an arm. His gun was slung over his stump, and he was constantly adjusting it as he shuffled down the alley. Cameron ducked and shifted every time the gun momentarily came to rest pointing at him.

It was like looking at ghosts in a way. They had essentially called a death sentence upon themselves by picking up guns in this environment. This young man would be killed by Israeli soldiers in the next few months. Nick would see his face on a poster.

We walked to the Yasmina Hotel. An Egyptian film from the sixties was playing in the lobby. Cameron did a double-take when he saw it. The women wore skimpy clothes and the main character, played by Egyptian actor Adel Imam, looked and acted like Cheech Marin.

“Things were a lot more liberal and laid-back in the sixties and seventies,” I explained. “The religious revival didn’t really start until after Israel defeated the secular Arab nationalists in 1967.”

When we got to our room, Nick asked Cameron what had struck him most during his stay in the West Bank.

“Those kids with the names of their villages around their necks in the Dheisha Refugee Camp,” he said. “Israel will never let the refugees return. It would mean the end of Israel as a Jewish-majority democracy. But the way those kids are being brought up, I don’t see how they can be happy without it. With that kind of thinking, I don’t see how there can ever be peace.” He shook his head bleakly. “It’s a lot more hopeless than I thought.”

I couldn’t help but reflect on the irony of the fact that he was criticizing the refugees for their inflexibility in demanding their rights, when he was just as rigid in his unquestioned belief that their rights must necessarily be denied.

(To read the full entry on Pamela’s blog, click here. To learn more about Fast Times in Palestine, see the book’s website.)

– Pamela Olson grew up in small town Oklahoma and studied physics and political science at Stanford University. She lived in Ramallah for two years, during which she served as head writer and editor for the Palestine Monitor and as foreign press coordinator for Dr. Mustafa Barghouthi’s 2005 presidential campaign. She contributed this article to PalestineChronicle.com.

I can only be thankful and grateful to Ms Pamela Olson bravery and courage. That how a young lady risks her life and future to help understand the world that how the Palestinian are living in an apartheid state called Israhell.