By Benay Blend

In January 2021, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) announced a global campaign “Facebook, we need to talk” about the social media giant’s inquiry into whether criticism of the movement Zionism “falls within the rubric of hate speech as per Facebook’s Community Standards.”

In its current form, the controversy centers around forcing universities, social media platforms, and other public spaces to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) standard which defines current anti-Semitism to include “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g., by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor” and “applying double standards” to Israel, overall a definition that would essentially shut down any criticism of the Zionist state.

According to Lara Friedman, the goal of Zionist groups who are pushing for this action “isn’t to get Facebook to deplatform antisemitism, but to get Facebook to deplatform criticism of Israel.”

In response, hundreds of activists, intellectuals and artists from around the world have launched a petition to ensure that Facebook does not include “Zionist” as a protected category in its hate speech policy—“that is, to treat ‘Zionist’ as a proxy for “Jew or “Jewish.” In its first 24 hours, the open letter gathered over 14,500 signatures, including such figures as Hanan Ashrawi, Norita Cortiñas, Wallace Shawn and Peter Gabriel.

“Cooperating with the Israeli government’s request,” the petition notes, “would undermine efforts to dismantle antisemitism, deprive Palestinians of a crucial venue for expressing their political viewpoints to the world, and help the Israeli government avoid accountability for its violations of Palestinian rights.”

These points are particularly critical as the International Criminal Court is moving towards investigation of Israel for war crimes, hence any coverage of this inquiry would be deemed anti-Semitic. Moreover, the effort to use the term Zionist as a place-holder for the Jewish people implies that all Jews think alike, which in and of itself is a racist stance no matter what group is being referred to in the argument.

Such statements as “all Blacks are….,” “all women are….” and so on are considered essentialist lines of reasoning that do not allow for free will and usually reduce the targeted population to the worst possible common traits. It trivializes the anti-Semitism that does exist, so when that bigotry is pointed out the response might be an unwillingness to believe the accusation.

Accordingly, conflating Zionism with Judaism does nothing to make Jewish people safer from racist comments. Indeed, as the petition argues,

“those who fuel antisemitism online will continue doing so, with or without the word “Zionist.” In fact, many antisemites, especially among white supremacists and evangelical Christian Zionists, explicitly support Zionism and Israel, while engaging in speech and actions that dehumanize, insult, and isolate Jewish people.”

Equally egregious, to oppose Facebook’s move solely on the basis of free speech places Western concepts at the center when it is really Palestinians who are deprived of their rights under the Occupation.

Freedom to support pro-Palestinian causes without fear of harassment from Zionist groups, as well as government reprisal, is, of course, an important issue. In the past, the free speech focus has been a tactic on the part of liberal groups who want to attract a wider audience. Nevertheless, it places concerns of the dominant groups at the center, our right to free speech, while Palestinians lack much more significant rights in their daily lives.

This attempt to stifle anti-Zionism is part of an emerging pattern by Israel and its supporters, but so far this has been limited to censoring conversations around the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS) based on fear of the campaign’s real success. It seems, however, that efforts to criminalize speech have been broadened to include any criticism of Zionist practices.

According to JVP’s petition, this latest effort would

“prohibit Palestinians from sharing their daily experiences and histories with the world, be it a photo of the keys to their grandparent’s house lost when attacked by Zionist militias in 1948, or a livestream of Zionist settlers attacking their olive trees in 2021. And it would prevent Jewish users from discussing their relationships to Zionist political ideology.”

“Whether Facebook will buckle under the pressure,” Friedman notes, depends upon “whether the public—Jewish and non-Jewish—finally recognizes that concerns about antisemitism are being exploited to serve a narrow political and ideological agenda, putting at risk free speech on Israel/Palestine and, by extension, political speech writ large.”

Defined by Steven Salaita, anti-Zionism is “a politics and a discourse, sometimes a vocation, but at its best it is also a sensibility, one attuned to disorder and upheaval. It is a commitment to unimaginable possibilities—that is, to realizing what arbiters of common sense like to call ‘impossible.’”

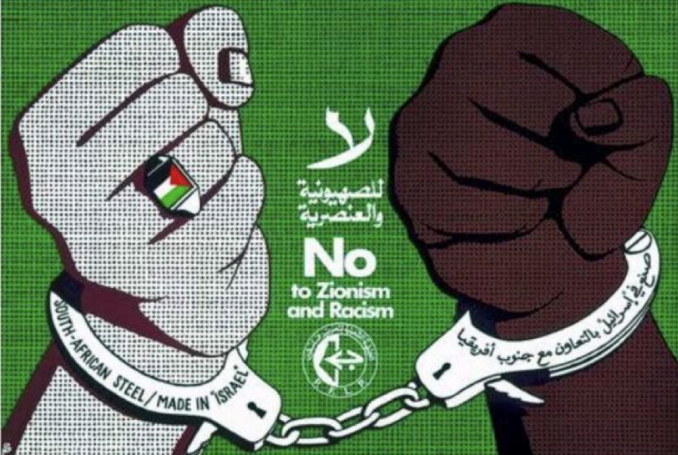

In a rebuke to those who equate anti-Semitism with anti-Zionism, Salaita affirms that “it [anti-Zionism] opposes all forms of racism, including anti-Semitism. This principle on its own decisively rebukes Zionism.”

If more people would abandon the politics of the “possible” in favor of Salaita’s call; if more people not only sign JVP’s petition but also organize protests in front of their local Amazon headquarters, it might be possible to make their voices heard.

Moreover, turning the tables by using the very medium threatening to censor anti-Zionism to educate the public about the reality of the Occupation might bring about the very thing that the Zionist most fear—one secular state with equal rights for all.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

– Benay Blend earned her doctorate in American Studies from the University of New Mexico. Her scholarly works include Douglas Vakoch and Sam Mickey, Eds. (2017), “’Neither Homeland Nor Exile are Words’: ‘Situated Knowledge’ in the Works of Palestinian and Native American Writers”. She contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.