It is often said that history is written by victors, however, it is forgotten that the same frequently applies to language. Embedded in the intrinsic fabric of etymology is populism, majoritarianism, injury, propaganda, imposition, and manipulation.

It is not to say that all linguistic legacy of the marginalized, the defeated and the oppressed are lost – with something as precarious and idiosyncratic as language, one never knows what might persist, leave a lasting imprint, regress, or resurge.

The corpus of language is a rising and ebbing ocean, or rather a featureful course of a stream. But English is replete with instances of conspicuous, glaring biases becoming apparently, or more dangerously, insidiously encoded in everyday parlance. Several such notable elements of speech have perpetuated archaic biases and stereotypes.

These biases are not all arbitrary – they exhibit certain patterns and an overall systematism, which albeit loose, is unmistakably identifiable. Most such biases are rooted in Eurocentrism and transmit historical European viewpoints and archetypes.

Certain origins are plainly, intuitively obvious – “To Go South” is a testament to the orientation of maps. The United States and Europe lie in the North, hence the phrase “To Go South” meant going down or deteriorating. Some attribute it to a Native American euphemism for dying, although that is unlikely.

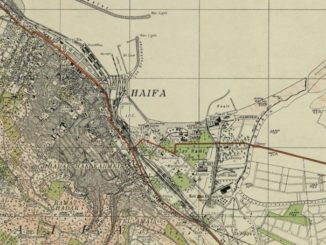

Judeo-Christian influence is highly palpable – “Philistine” is an epitome. The word “Philistines” referred to the people of the land of Philistia (Hebrew P’lesheth). As would be phonetically obvious, it is closely related to the word Palestine – they share the very same origin from Hebrew via Greek.

In the old testament, they were the inhabitants of coastal Palestine and waged war against the Israelites, purportedly harassing them. In fact, the ultimate root of the Hebrew word P’lishtim (demonym for P’lesheth) means “to assail, migrate, or invade”.

Philistine is supposed to have been used as a humorous figure for enemy in English since circa 1600. The present sense of usage of the word i.e. “person deficient in liberal culture and artistic appreciation” stems from German student slang, where the term was a derogatory term for burghers or “townies”.

Its pejorative nature, in turn, comes from German Philister which stood for “enemy of God’s word”. It is speculated that the use of Philister for townsfolk owes to an incident from 1693. The biblical text “the Philistines be upon you, Samson” was used in a memorial service for a Jena University student who had died in a town and gown dispute.

However, the antagonizing bias is not merely limited to the Judeo-Christian narrative.

“Barbaric” meaning “uncultured, uncivilized, unpolished” reflected the Roman perception of all around them as savage brutes with obtuse and uncouth demeanor and a coarse and blunt disposition. Notwithstanding the fact that Romans engaged in enslavement, conquest, torture, and bloody arena battles, the inherent contempt came to augmented and perpetuated in English nomenclature.

Initially, despite carrying undeniable connotations of incivility and savagery, the Latin “barbaricus” meant “foreign, alien, strange, outlandish”, only alluding to, not outright meaning brutish. The Greek predecessor “barbaros” meant rude, but not gross, just indecorous and discourteous.

The term “Berber” is a variant of the Greek original word “barbaros” (“barbarian”). Initially, the Romans had specifically applied it to their hostile neighbors from Germania and even the Celts, Gauls, Iberians, Goths and Thracians. Such is the ingraining that even today a ruthless or brutal act is condemned as being “barbaric”.

The Berber community is an ethnic group indigenous to North Africa and parts of Northwest Africa. The original nomadic inhabitants of the land, the ancestors of the current people, were long in friction with the Ancient Greeks.

Since antiquity, they came in occasional competition, and even conflict with the neighboring civilizations. The civilizations in their vicinity disapproved of their shifting, unsettled, tribal ways.

The word crept in Arabic and became the main word used to refer them in multiple language families. In fact, the word’s pejorative lineage precedes the Ancient Greek.

The Proto-Indian word “Berber” used to refer to any Non-Aryans and people who didn’t speak their language. In fact, the word was carried as such in Sanskrit and subsequently in Hindi, and today is used in common language to refer to something cruel, tomentous and merciless.

The Greek Barbarus also gave rise to Latin barbaria (lit.”Foreign Country”) and in turn to Medieval Latin barbarinus, acquiring its current meaning. Over time, both “berber” and “barbarian” were employed by various European civilizations to refer to any enemy who was not a proper urban civilization.

The Romans could label any forest-dwelling foe such, while Christian Empires would contemptuously refer so to Pagans, cultists and nature worshippers.

A similar fate was suffered by the Goths, an East Germanic tribe who had a distinct enmity with Rome, suffered a similar fate.

Despite establishing multiple states in the latter’s wake, constituting a systematic cultural corpus, and devising a distinct, salient, and eminent architectural form that served as a major influence all over Europe and later even in its colonies, the Goths could not escape the Roman labeling and connotation as enemies of civilization and order.

“Goth” came to be synonymous with “Berber”. Another East Germanic tribe, that of the Vandals were one of the many people who’d been suppressed and vilified by the Romans. Romans came in conflict with them due to their territorial expansionist ambitions and the denial of the Germanics to exploit resources of the land that they held as rightfully theirs.

As Rome declined, the Germanic tribes drove the final nails in the coffin, committing loot and plunder. Priest and revolutionary Henry Gregoire used the French version of the term, vandalism, to decry the pillage and destruction of art during the French Revolution.

Over time, any willful act of damage, desecration or destruction of heritage, culture, art or even property came to be known as vandalism. Today, “Vandal” is interchangeable with “Goth” used to disapprove a boorish person, or someone who seems to lack creative or critical sensibility.

Talking of boorish, the word was borrowed from the Dutch word for peasant – boer. This is one of the numerous instances of trivialization and derision of the basal portions of the feudal hierarchy – people who were met one of the invariably two fates – neglectful condescension or convenient, unopposed scapegoating. It’s not just English.

In Hindi, the word “Ganwaar”, literally meaning a village-dweller has invariably set to a pejorative for an illiterate, uncouth or uneducated person. The stereotypes are further reinforced with each instance of usage of the word – cementing with each impoundment.

“Ionian” (referring to the residents of the eponymous Greek islands) was borrowed via ancient Persian into Sanskrit and transformed to the pejorative “Yavan” which was used in Pre-Islamic India to refer to everyone from a mythological demonic nemesis of Krishna to the Greeks to the early Muslims and even the Europeans.

From “dexterity” meaning “right-handedness” or “right-sidedness” as well as “skillfulness” and “deftness” (an obviously majoritarian construct disregarding the identity of left-handers) to “plebeian” taking on a connotation of “vulgar and unrefined” from originally simply referring to the common citizenry (a norm exhibited by most words referring to commoners), the immense sway wielded by words seem to easily succumb to popular and dominating narratives.

If anything, the afore quoted examples testify to the proneness of society to language and the proneness of language itself. It is important to use words responsibly – for each individual usage, no matter how instance-specific, shifts the circle – the center, the umbra and the penumbra of its general conception, comprehension and understanding.

– Pitamber Kaushik is a columnist, journalist, writer and researcher. He contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle.

A must read article.

I read that the Greek barbaros came from the Sanskrit barbaras ‘babbling’, meaning to stammer (or say ba-ba-ba), this being how the Greeks viewed peoples whose language they couldn’t understand. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbarian#Semantics