By Issa Boulos and Louis Brehony

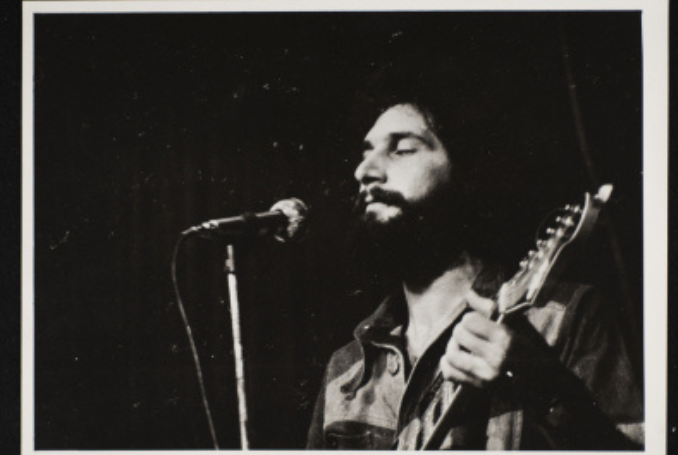

“Anā ismī shaʿb filisṭīn” – my name is the Palestinian people. Song lyrics that would ring out in the refugee camps and university campuses, from quickly duplicated cassettes sold by the thousand. Their singer, George Kirmiz, gave voice to the suffering and revolutionary aspirations of a generation growing up in the 1980s.

From making songs out of the rebel poetry of Tawfiq Zayyad and Mahmoud Darwish to original lyrics targeting imperialism and colonialism, Kirmiz’s vocals floated over sounds that were new to the Palestinian context, underpinned by guitar, piano, and occasional ʿūd (“oud,” or short-necked lute used across the region). His recordings became anthems of the dispossessed in years before the 1987 intifada but, after a flurry of tapes, the music stopped. A career cut short.

But who was George Kirmiz? A guerrilla on the front lines? A political prisoner? A non-Palestinian singing out of solidarity for Palestine in his own country? Discovering Kirmiz’s identity and whereabouts has preoccupied many listeners. In June 2022, reports on Palestine TV and the State of Palestine website marked ‘40 years’ since the musician’s ‘disappearance’, with little in the way of factual backing for the assertion. Others have looked long and hard and concluded that nobody would ever know who Kirmiz was. He was the Palestinian people, his song proclaimed in collective identification, from Turmus Ayya, Ṭabariyya (Tiberius), Arab Jerusalem. Or, in the words of Rashid Hussain, sung by Kirmiz over ʿūd on one cassette:

I, cloud of my life, am the hills of al-Jalīl (Galilee),

I am the bosom of Ḥayfā (Haifa)

And the forehead of Yāfā (Jaffa).

Busting a few prevalent myths, this article previews our respective research, which will be published over the coming period. We aim to offer clarity for the first time on the life and singing and songwriting career of George Kirmiz.

Born in Jerusalem in March 1953 to a Palestinian Syriac Christian community in the Armenian quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, Kirmiz attended St. George’s School, a British boys’ school in East Jerusalem, run by the Anglican Diocese of Jerusalem. Growing up in poverty, he learned how to play guitar as a teenager and joined the group al-Baraem in 1971, where he played guitar and sang. Although it is unclear when he started composing, al-Baraem violinist William Voskergian reports that Kirmiz wrote the song “Iʿtidhār ʿAn Khalal Fannī Ṭāri’” (“Apology, for an urgent technical difficulty”) to poetry by Haydar Muhammad. A live performance of the song at Bethlehem University in 1976 was captured on a cassette recorder. Band co-leader Emile Ashrawi recalls that Kirmiz presented a portion of the song to the group during rehearsal, and Ashrawi helped him finish it. The song points to various musical and stylistic characteristics that Kirmiz shared with al-Baraem and other sonorities and textures that he explored later in his career.

Supported by older brother Mark, a biochemistry graduate from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, Kirmiz moved to the US in 1976. However, Mark didn’t enjoy working in the field and instead opened a shoe repair shop in neighboring Ypsilanti. Between long hours and some unique stock investment strategies, Mark did well financially. George worked long hours in his brother’s shoe repair shop.

During this time, Kirmiz became very active in the Ann Arbor area in Michigan, and collaborated with various musicians, including pianists M. Abdein (on the “Anā Ismī Shaʿb Filisṭīn” album) and Randal Faber, who recorded with him between 1980 and 1984, double-bassist Glenn Bering, who appeared on many of his recordings and some of his concerts, and percussionist Bob Cranmer. Remaining in the US, he recorded four albums and toured frequently until the mid of the 1980s.

Kirmiz gained popularity among Palestinian audiences in the United States, Europe, and the Arab World. He appeared at Palestinian student events and was associated with the left. According to supporter Waem Garbieh, the DFLP “considered him one of us,” and bought Kirmiz his first ʿūd, partly in an attempt to recruit him to the organization. One of the many political events in which he performed was the June 1983 national conference of Palestinian students in Chicago. Then student activist Rami Rasheed remembers Kirmiz singing his ode to Jerusalem:

Oh Jerusalem, my city

By my notebook, my pen,

and the fire of my rifle,

We will raise the flag.

Kirmiz’s 1985 album “Min Anṣār Ila-ʿAsqalān” (“From Ansar to Asqalan”) was directly dedicated to the cause of political prisoners, responding to the recent designation of 17 April as an annual day of solidarity with Palestinians locked up in Zionist jails. Its sleeve notes read:

“I consider this humble artwork as a means to commemorate this occasion and dedicate these songs to all of the Palestinian fighters in the Israeli prisons, and to all Arab political prisoners in the clutches of the reactionary Arab regimes, who stand with their heads held high in hope for a better tomorrow for our Arab homeland.”

In most of his songs, Kirmiz relied on Western instruments, compositional devices, harmonies, and form. Kirmiz mainly composed poetry in standard Arabic by Palestinian poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Rashid Husain, and Tawfiq Zayyad. Most of these poems were already widespread, a trend many songwriters utilized to popularize their songs. In addition, he wrote and set to music poems in standard Arabic and lyrics in mostly colloquial Palestinian dialect. Kirmiz worked on his music with the group and would bring in songs in finished form. According to Faber,

“He (Kirmiz) wrote all lyrics and melodies and used either guitar or piano to find the harmonies. He was quite directive of the sound he wanted, typically demonstrating himself on various instruments. He used the tabla to show rhythms and would often demonstrate on the piano the sound or style he wanted.”

Kirmiz also modestly played the ʿūd, adding some “quarter tones” to his singing and melodies, a feature absent in al-Baraem’s and Kirmiz’s early songs. Faber recalls that Kirmiz was a strong leader who knew what he wanted and envisioned the form of his songs in detail. He produced all his albums at Brookwood studios in Ann Arbor with recording engineer David Lau.

Among Palestinian commentators, there has been intense speculation over the reasons Kirmiz stopped performing and recording. While he continued to sing at concerts in the early years of the 1987-1993 intifada, he told band members he intended to retire. His final album in 1985 had hinted at his direction:

When the words end

and my songs dry out

The homeland remains the last word

and all of the songs

(“Lamma Btikhlaṣ il-Kalimat,” “When the words end”)

Kirmiz was a superstar on tour and a shopkeeper during the day. A craftsman who maintained the humility of his roots. When his brother retired early, George took over the shop and focused on custom shoe work. He eventually sold the business and retired incognito at a young age. Faber last saw Kirmiz in 1990 when he retired and moved away from Michigan. He’d settle in Paradise, California, where he opened a shoe repair shop in Chico, 13 miles away from his home. Unfortunately, the shop was permanently closed during the pandemic.

– Issa Boulos was born in Jerusalem and is an international award-winning composer, lyricist, songwriter, and researcher. Issa has performed and led musical ensembles in Palestine and across the world. He received his Ph.D. from Leiden University and currently serves as Community Music Center Coordinator at Harper College, Chicago. He plays oud, and buzuq.

– Louis Brehony is a Manchester-based musician, activist, researcher, and educator. He is the director of the award-winning film Kofia: A Revolution Through Music (2021) and the author of an upcoming book on Palestinian music in exile. He writes regularly on Palestine and political culture and performs internationally as a guitarist and buzuq player. They contributed this article to The Palestine Chronicle